HISTORY

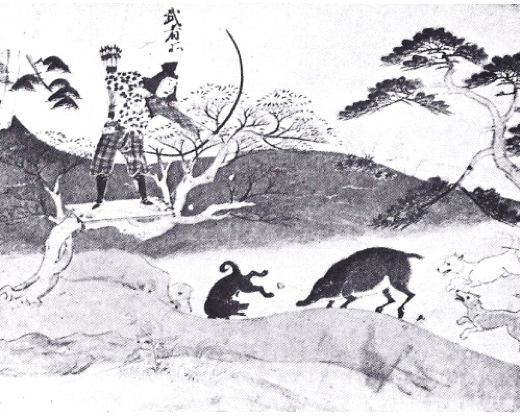

The Akita dog breed originates from the Akita prefecture in northern Japan and has been present for up to 1,000 years. In the 1600s, Akitas were involved in dog fighting, a popular sport in Japan at the time. However, during the early 20th century, the breed faced a decline due to crossbreeding with German Shepherds, St. Bernards, and Mastiffs. This crossbreeding led to the loss of many traditional spitz characteristics, resulting in drop ears, straight tails, non-Japanese colors (such as black masks and colors other than red, white, or brindle), and loose skin.

To restore the breed's original spitz phenotype, native Japanese breeds like the Matagi (a hunting dog) and the Hokkaido Inu were reintroduced to the remaining Akitas. Today, modern Japanese Akitas retain their spitz characteristics and have minimal genetic influence from Western breeds due to these restoration efforts. In contrast, the larger American Akita, which descended from the mixed Akitas before this restoration, typically exhibits characteristics that differ from the Japanese standard and is often considered not to be a true Akita by Japanese standards.

During World War II, the Akita was crossbred with German Shepherds to help preserve the breed in response to a government order that mandated the culling of all non-military dogs. The ancestors of the American Akita were originally a type of Japanese Akita with markings that were not favored in Japan and were therefore not eligible for show competition.

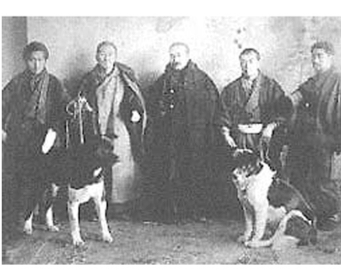

In 1931, the Akita was officially declared a Japanese Natural Monument. To preserve the original Akita as a national treasure, the Mayor of Odate City in Akita Prefecture established the Akita Inu Hozonkai, dedicated to careful breeding. In 1934, the first Japanese breed standard for the Akita Inu was established following the breed's recognition as a natural monument.

In 1967, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Akita Dog Preservation Society, the Akita Dog Museum was built to house information, documents, and photographs related to the breed. Additionally, in Japan, it is traditional for a child to receive a statue of an Akita upon birth. This statue symbolizes health, happiness, and a long life.

In 1937, Helen Keller traveled to Japan and developed a strong interest in the Akita breed. During her visit, she was presented with the first two Akitas to enter the United States. The first, named Kamikaze-go and presented by Mr. Ogasawara, sadly died of distemper at just 7½ months old, one month after Keller's return to the U.S. A second Akita, Kamikaze’s litter brother Kenzan-go, was arranged to be sent to Keller. Kenzan-go also passed away in the mid-1940s.

By 1939, a breed standard for the Akita had been established, and dog shows had begun, but these activities ceased with the onset of World War II. In the Akita Journal, Keller wrote:

"If ever there was an angel in fur, it was Kamikaze. I know I shall never feel quite the same tenderness for any other pet. The Akita dog has all the qualities that appeal to me—he is gentle, companionable, and trustworthy."

As the Akita breed was stabilizing in its native land, World War II pushed it to the brink of extinction. Early in the war, the dogs suffered from a lack of nutritious food. Many were subsequently killed to be eaten by the starving populace, and their pelts were used as clothing. Eventually, the government ordered that all remaining Akitas be killed on sight to prevent the spread of disease.

Concerned owners sought to save their beloved Akitas by either releasing them into remote mountain areas, where they interbred with the Matagi dogs, or by hiding them from authorities through crossbreeding with German Shepherds and adopting German Shepherd-style names. Morie Sawataishi’s efforts to preserve and breed the Akita played a major role in ensuring the breed’s survival.

During the occupation years following World War II, the Akita breed began to recover thanks to the efforts of Morie Sawataishi and other dedicated enthusiasts. For the first time, Akitas were bred to a standardized appearance. Japanese fanciers started gathering and exhibiting the remaining Akitas, producing litters to restore the breed's numbers and emphasize its original characteristics, which had been diluted by crossbreeding with other breeds. U.S. servicemen who had developed a fondness for the Akita imported many of these dogs upon their return, further contributing to the breed’s resurgence.